The pitfalls of ESOP lifelines at startups

Before they started Udaan, a marketplace platform that facilitates trade between businesses, in 2016, the company’s three founders, Amod Malviya, Sujeet Kumar, and Vaibhav Gupta, had completed successful stints at Flipkart. The three were among the biggest beneficiaries of Flipkart’s generous employee stock ownership plan (ESOP). By 2016, they had already received substantial sums through selling some of their holdings in Flipkart’s periodic stock buyout programmes conducted for employees.

With Udaan (Hiveloop Technology Pvt. Ltd), the three of them wanted to build a Flipkart-type internet firm for businesses and in record time. So they adopted some of the best practices they had learned at the online retailer, one of which was a large ESOP programme. Udaan’s ESOP policy was even more radical than Flipkart’s—bigger but, more importantly, far more demanding employees. The first two dozen employees who joined the company were offered salaries more than 50% lower than their previous jobs instead of a large award of ESOPs.

“We started by giving low salaries because we wanted to conserve cash to invest in the business as we didn’t have that much money when we had started. We gave enough salary that people did not have to compromise on their lifestyle, and they could run their day-to-day lives comfortably,” Kumar said.

Over time, Udaan moved closer to market rates but still offers lower cash payouts to its 3,000 employees than peers and continues to rely on ESOPs as its biggest carrot. The ESOP policy allowed Udaan to pour more capital into the business, which has grown at a prodigious rate, touching more than $2 billion in annualized gross merchandise value (GMV) at the end of 2019. Its valuation soared to $2.8 billion last year, the clearest indicator yet that the company’s ESOP policy may work out well for employees.

Udaan’s ESOP policy is hardly a new idea; it’s a textbook approach to compensation that is popular with startups in the US and China. This approach, however, is very rare in India’s startup ecosystem, where most employees refuse to accept stock options instead of cash salaries. At Udaan, unique factors enabled its ESOP policy: most of its early employees had personally benefitted from Flipkart’s ESOP policy, and the three Udaan founders led by example by forgoing cash salaries thetrica equitylves.

Such a fortuitous combination is unlikely at most other startups, which end up having to shell out huge cash sums to attract top talent. Yet, over the past three months, Oyo, Zomato, Bounce, CarDekho, Grofers, and other companies that have been hit by the pandemic (Grofers only suffered a temporary hit) have thrust ESOPs upon employees whose salaries were cut. Even those fired at these and other companies like Swiggy and Ola have been offered accelerated vesting of ESOPs.

This sudden recourse to using ESOPs by so many startups was prompted by their need to conserve cash as revenues collapsed.

But it is far from clear whether this works out well for startup employees, who continue to regard the ESOP rewards with scepticism. And with good reason, as there are no standard practices followed by startups around ESOPs where finer, legalistic details make all difference, according to entrepreneurs and executives.

“I don’t think there will be much of a change in the way startup employees look at ESOPs, either positively or negatively,” said Abhishek Goyal, co-founder, Tracxn, a data platform. “Very few people have a deep understanding of how options work. Even among senior executives, the understanding of ESOPs is not developed. This won’t change any time soon.”

Subramanya S.V., the founder of financial technology startup Fisdom, likened the policy of reducing salaries and giving options instead of “slapping someone and then offering them 100 bucks to go to the doctor.”

“The pain of salary cuts is real, and unless the ESOP policy in these cases is really friendly toward employees, these announcements are little more than PR (public relations) exercises. Having friendly policies means keeping strike prices very low and allowing employees to be able to vest shares when there’s a liquidity event,” Subramanya said.

Devil in the details

Here’s how ESOPs work: If an employee is awarded 100 options, these options vest in intervals, say 25 options every year, over four years. Once the options vest, the employee can convert them into actual shares. Many startups allow employees to convert these shares for a nominal price like ₹10 or ₹100. But some startups keep this so-called strike price at high levels, closer to the per-share value in the last funding round, which discourages employees from exercising options.

Perhaps, the most important clause in ESOP policies is the expiry period. Because of taxation rules, most employees prefer to convert options into shares only at an actual liquidity event. Many companies, though, keep a short expiry period on options, which means that if the employee decides to leave the firm, they will have to convert the options into shares within weeks of their last day.

Mint asked the companies that have recently replaced part of employee salaries with ESOPs about the terms of their ESOP policies. A Grofers spokesperson said the company had awarded employees who voluntarily took temporary salary cuts with ESOPs worth 12 times the foregone salary. In addition, half of the ESOPs were “pre-vested”—almost as good as shares—while the other half have accelerated vesting. Now, the company’s ESOP pool accounts for 11% of Grofers stock.

Grofers’ large ESOP pool and generous terms are an exception. A majority of large internet companies restrict their ESOP pools to 2-7% of the overall shareholding to protect the interests of founders and venture capitalists (VC). Hence, the sudden about-turn by companies draws a roll of the eyes, especially as valuations of many startups are certain to be eroded by the pandemic.

“In cases where the long-term outlook for the company is not looking good, employees will naturally not be happy about getting more ESOPs,” said Sanjay Jha, co-founder, and product chief, LetsVenture, an investment platform. “Also, employees at lower salary levels would not appreciate losing any cash component of their salary instead of ESOPs. But those employees who believe that the startup will be successful over the long term will not mind getting more ESOPs. They were believers in the company, and they would now think that they can make more money in the long run by getting more ESOPs.”

Down rounds hurt the ability of startups to use ESOPs as a compensation tool both to attract and retain people, said Fisdom’s Subramanya, a former VC. “With down rounds, existing ESOP holders know that their options and shares have declined in value. Besides, down rounds also restrict the ability of companies to use ESOPs to attract fresh talent (because the ESOP pool automatically becomes smaller),” he said.

Systemic problem

ESOPs in India is a typical example of a systemic problem.

Startups typically benefit when their early employees agree to join at very low salaries. For absorbing this income loss and assuming the risk of joining an unproven venture, employees are awarded large quantities of stock options that could grow exponentially in value if the startup does well. In this structure, everyone benefits—staff is incentivized to work hard and stay loyal to the startup, as its success would create enormous wealth. In contrast, the startup ends up saving precious cash in its early stages when capital is scarce. Some of the most successful internet companies in the world, including Google, Facebook, Amazon, Alibaba, and Flipkart, have reaped the benefits of this approach.

Eventually, for ESOPs to work, exits, either through an IPO or a sale, are key. And the fundamental problem for Indian startups with regards to ESOPs, and, in general, is that there just haven’t been enough exits.

Flipkart’s $16-billion sale to Walmart in 2018 was by far the biggest success story in the startup ecosystem, but it was the exception. Despite the billions of dollars that have been invested in startups every year since 2014, the returns for investors have been meager, and few startups are in any shape to go public.

Because of the paucity of exits, employees, who are last in the pecking order of stock beneficiaries, haven’t seen consistent proof that ESOPs are the wealth-creation tools they are made out to be. On the other hand, the implosions at once-flying startups like Snapdeal, Shopclues, and Housing have served as cautionary tales that ESOPs are the proverbial pie-in-the-sky.

“People want options, but they are not willing to take discounts on their previous salaries, so they see ESOPs as toppings to salaries, rather than cash replacements,” said Tracxn’s Goyal. “It’s a funny situation because almost all startup employees want ESOPs, but few of them actually understand ESOPs or make an effort to know more. So a lot of ESOPs often get wasted.”

Employers, too, struggle to get the best out of an ESOP program, he added.

“In recent years, ESOPs have become a yardstick of whether employers treat employees fairly because everyone has heard about ESOPs. But the return on investment in ESOPs is low for employers because employees aren’t willing to take lower salaries, and the ESOPs don’t necessarily make them feel incentivized to stick on at the company,” Goyal said.

There are few norms around handling ESOPs in the startup ecosystem. Some companies that orally tell their employees about options fail actually to give them the requisite ESOP documents. Startups include clauses that allow them to withhold vesting. ESOP management is a mess, too, and companies often keep loose records of ESOP holders. All these factors contribute to the lack of faith in the stock instruments.

Need for liquidity

To be sure, some startups are making an effort to show that ESOPs are valuable instruments. Earlier this month, Oyo announced that it would buy back ₹200 crores worth of shares from some 600 employees. Mint learned that most of this buyback would go to a handful of senior executives whom Oyo is eager to retain. Still, the rest of the 600 employees, too, will receive at least some cash. Coming at a time when Oyo is fighting for its survival, it’s a brave move by the firm.

Taking a cue from Flipkart, which conducted regular stock buyback programmes for employees years before its sale, some startups have begun arranging share sales for staff. Over the past few years, unicorns like Paytm, Ola, Swiggy and Rivigo have conducted stock buyback programmes for employees worth hundreds of crores of rupees. Udaan’s Kumar said that the company plans to arrange share sales for employees within two or three years. Even smaller companies like Unacademy, Razorpay, UrbanClap, and CarDekho have offered liquidity to dozens of employees. In these transactions, either the company buys back stock from employees or arranges a stock sale for employees with VCs.

This year, the central government has announced tweaks to taxation rules that will defer the tax burden and potentially make ESOPs more attractive for startup employees.

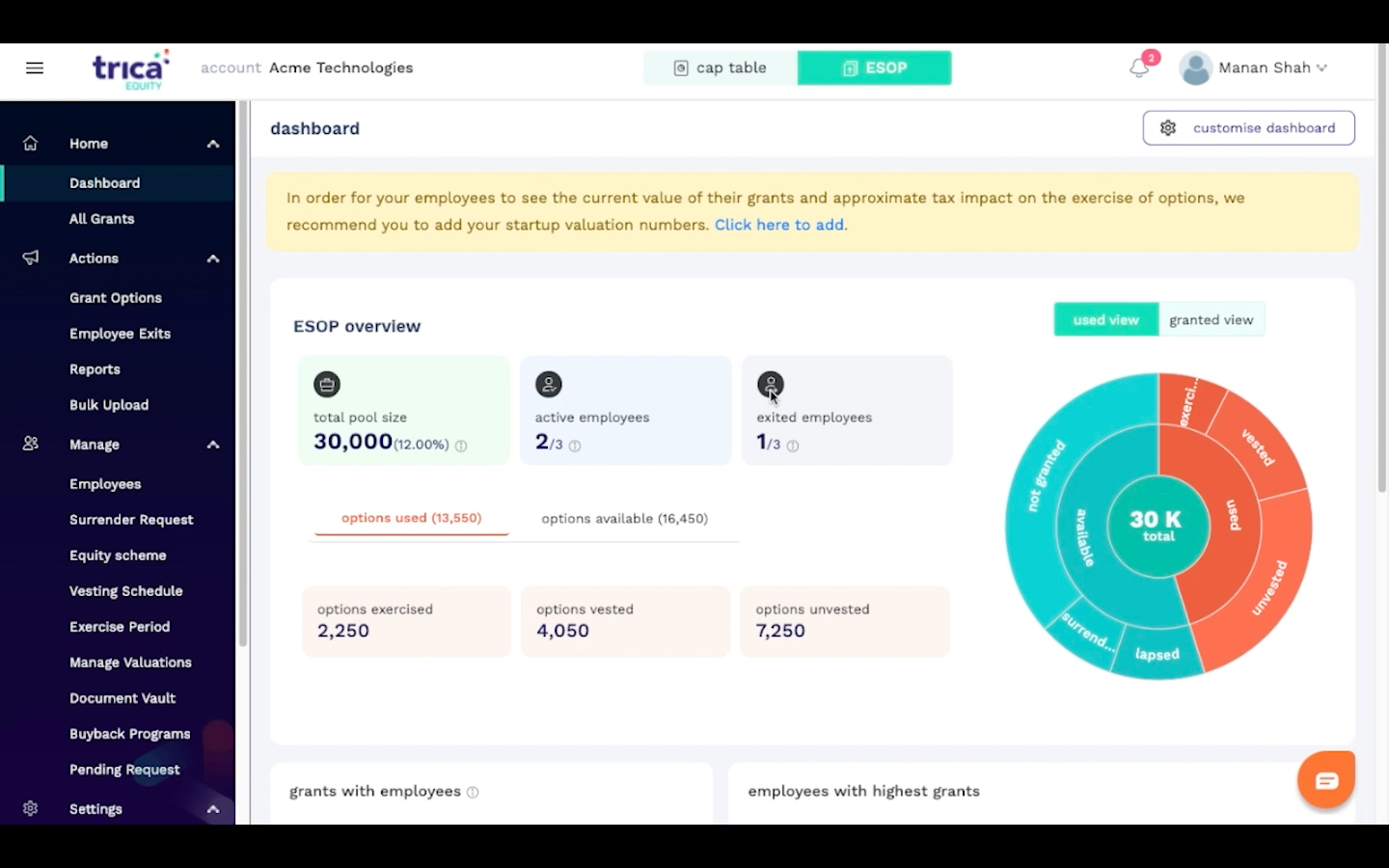

Some firms and investors are now working to create a market for ESOP transactions. Earlier this year, LetsVenture launched trica equity, a product for managing ESOPs and shareholder rosters at startups. Among its chief aims is to connect investors with startups to arrange stock sales for the latter’s employees. “With the covid crisis, usage of ESOPs has increased dramatically, so we think that the need for ESOP liquidity and management via a product will also increase,” LetsVenture’s Jha said.

Published in LiveMint on June 17 | Source: https://bit.ly/30X7Bq2

Check out trica equity and manage your entire equity stack digitally!

Click here to understand how sweat equity works in India.

ESOP & CAP Table

Management simplified

Get started for free