ESOPs: What’s the ESOP DNA of your startup? #LetsTalkEquity

In this #LetsTalkEquity interview with TN Hari, Head HR of BigBasket – India’s most significant online food and grocery store, we deep dive into how you can think about ESOPs at your startup. Hari has been an HR practitioner and advisor to multiple startups and scale-ups and helped shape four successful exits in different industries, including an IPO on NASDAQ.

Presently, Hari is the Chief People Officer at Big Basket, an advisor to VCs like Arkam Ventures and The Fundamentum Partnership.

In this free-wheeling chat with Ganesh Nayak of trica equity, Hari talks about:

- How ESOP policies have evolved over the past decade

- Building a scalable ESOP policy and

- What can be done to maximize the impact of ESOPs at your startup

Ganesh: Being a practitioner and an advisor to CHROs in the ecosystem, what are some of the patterns or trends that you have seen over the last year or so as far as stock grants or ESOPs are concerned?

Hari: I think some companies have leveraged stock options smartly to attract and retain talent. On the other hand, some companies tried to use stock options but never really understood them – communicating value, ensuring grants are correctly made, and transparency. These companies completely frittered away the opportunity – they ended up granting stock options but didn’t attain the outcome of retention or attracting the best talent.

I think there are a couple of things that have changed broadly.

For instance, say that the fair market value is INR 1000 and the face value is INR 10, then in the past, the strike price would be INR 1000, but today, the strike price is INR 10. Therefore, though fewer options are granted today, employees can make a lot as the strike price is mainly set as the face value.

But if you ask me, the right way to do it would be to use a fair market value (FMV) because that is a fundamental principle aligned with the entire objective or purpose of having a stock option plan.

Let me elaborate on this a bit. The purpose of a stock option plan is an employee, at a very senior level, comes into the company and helps create value and take it from X to Y and should benefit from that growth. And the current fair market value is indicative of the growth. But the problem with that principle was that people who were grantees of stock options struggled to figure out what was in it for them, what value they were holding on to. So, for example, if you are granted 100,000 options and the strike price is INR 1000, you will make money only if the fair market value begins to climb, i.e., the company share price goes from INR 1000 to INR 1100, and so on. But I think grantees cannot make out the incremental value about how the stock price is moving. But if you give them options at face value, they have a way of comparing it with cash. So, the significant change introduced was that you can compute the value of what the company is granting you stock, compare it with the cash compensation, and make the trade-off.

Lastly, I would say that there are two types of employees:

- In their past companies or early in their career, those who have benefited from stock options have seen multiple liquidity events and have made money out of it. Therefore, they will trust your plan, and they will believe that they will make money.

- The second category of people have never seen any benefit through a stock option plan, and therefore they’re skeptical. They’re either open to exploring this, or they will only negotiate for cash compensation.

Ganesh: When you say that the exercise price has moved from fair market value to nominal value or face value, do you think other factors are at play here? Many listed companies issue ESOPs at fair market value and all the shareholders hold the same equity shares, and the stock exchange decides the fair market value. Do you think the fair market value at which employers granted ESOPs may not hold the same in private companies after a while? Investors have anti-dilution rights when companies go through a down-round, but this may not hold for ESOPs as the exercise price does not change, per se. What are your thoughts on these dynamics?

Hari: I think listed companies typically don’t leverage stock options; instead, they use RSUs or restricted stock units. RSUs are really granting shares, as the employee doesn’t have to pay anything at all. Let’s say you are working for Tata Steel or IBM, and the share price is INR 170, and you’re given 1000 shares; this means you get a value of INR 172,000. The employee is just granted shares in this regard.

Coming back to the other question that you raise, which is, what could be the different considerations for moving away? I think all these liquidity preferences, especially when later investors come and bargain for and negotiate, completely alter the kind of money that either employees or early-stage investors can make. And, you could argue both ways – if early-stage investors are at risk, but employees are like early-stage investors, right? So, the belief is that you never have to resort to the liquidity preference clause as that is the worst-case scenario.

If you ask me, early-stage investors and employees have taken a risk by choosing to work for a startup or to invest in a startup. And by being in the early stage, they also have an opportunity to make good money, and they are also subject to the same risk. But, on the other hand, late-stage investors bring in a massive amount of money and, therefore, want to be protected. So I think by granting ESOPs at face value, you are guaranteeing a reliable value creation for employees.

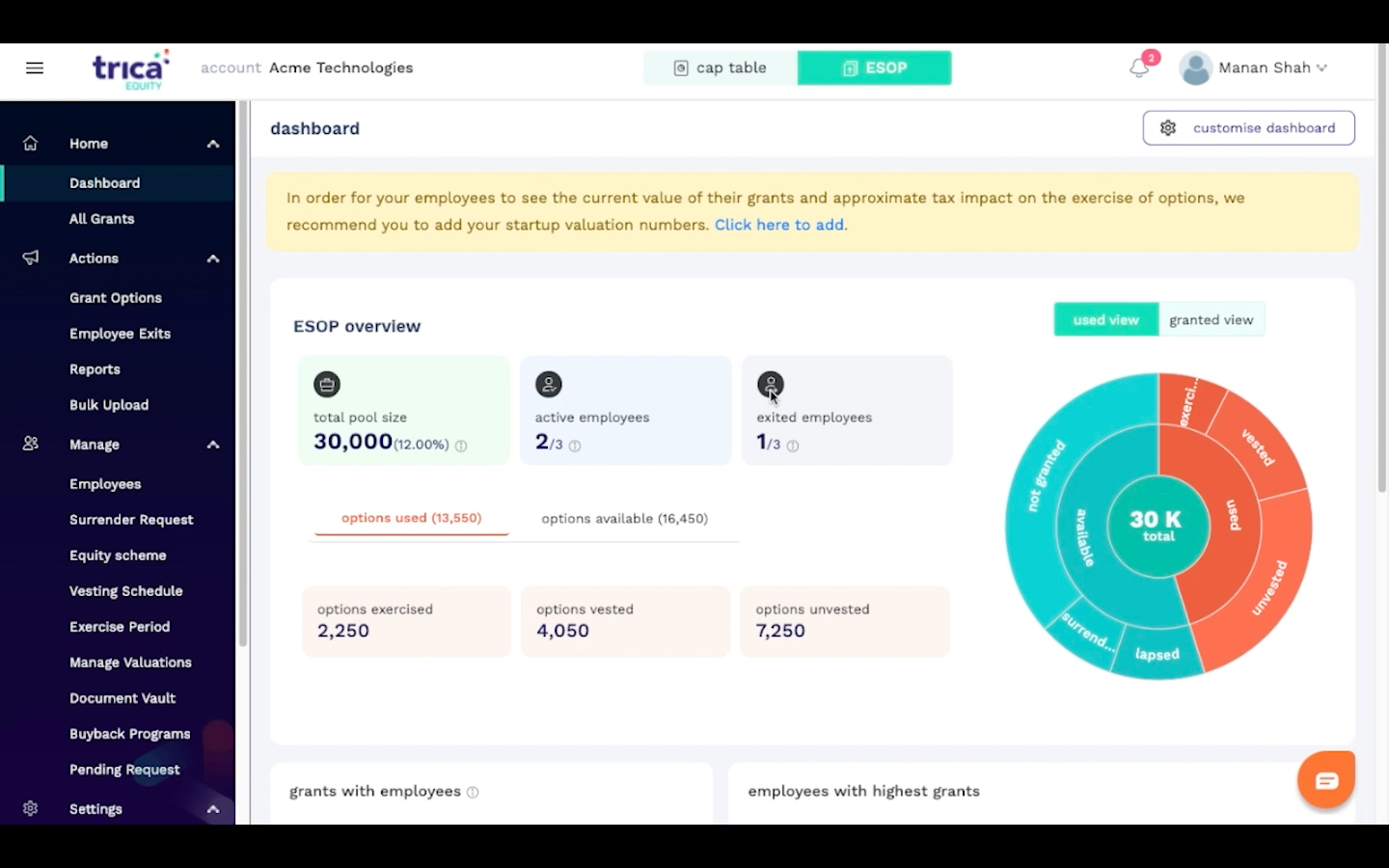

Ganesh: We can relate to the communication piece. At trica equity, many companies use the product so that their employees can log in and understand the value of the ESOPs they have and the tax impact that it will have. So we do see that gap. You mentioned two changes in the ESOP ecosystem. I want to ask you if there’s a third change in terms of the post-termination exercise period. A lot of employees have been asked to leave or have left for a variety of reasons. That’s when employees realize that employers give them a limited amount of time, maybe one month or three months or six months, to exercise vested ESOPs. This means that upon exercising, employees will have to bear the exercise tax. Have you also come across a debate in this regard, and what changes have you seen?

Hari: Some years back, employees were given 30 to 90 days to exercise their vested options after leaving the organization. And obviously, the tax that they had to pay upfront to exercise these options was quite steep, and as a result, many employees were leaving the stock options on the table and walking out.

I would say that in some ways, this acted as a hook to retain people, but it was a perverse hook. For example, suppose 75% of ESOPs have vested for an employee; now, the employee has to leave everything on the table upon quitting. So employees would decide to stay on till there’s liquidity. Ideally, companies should not want that kind of “incentive” to hold back employees. Nevertheless, all said and done, that was a common practice. But now, as the war for talent has become a bit steep and robust, some companies are becoming very flexible and generous on that front. They allow ESOP exercise for a longer time – let’s say ten years. In this case, the plan expires at the end of 10 years, and until then, the employee can exercise vested options even if they quit.

At BigBasket, for example, we have two stock option plans. One stock option plan is where we have set an expiry of 10 years. The second plan is slightly different – if the employee quits at the end of 3 years, they should exercise within 90 days. But if an employee hangs on for four years and lets all their ESOPs vest, we extend the plan to 10 years. These plans allow employees to craft their stock option plans.

Ganesh: In our last conversation, you had mentioned some thoughts about how wide the ESOP policy should be. Many large companies, even unicorns, give out ESOPs to every employee – maybe 1000s of employees. What are your thoughts on that? Has your perspective changed in terms of how broad or how narrow the ESOP policy should be?

Hari: My perspective hasn’t changed on this. Stock options are scarce and must be leveraged very wisely – ESOPs should not be granted to employees who do not appreciate the value. And I would go so far as to say that even at senior levels, when you’re recruiting, you don’t have to necessarily grant the same number of options to individuals who are at entry-level. If an employee is negotiating a very high cash compensation and not willing to budge versus somebody who appears okay with the lower cash compensation because this person believes the stock options will deliver. I think it does not make sense to waste a scarce asset resource on people who do not appreciate the value. So I’m still of the view that you shouldn’t be distributing stock options to a broad group of people. And if you are distributing it to the janitor in your company, maybe the janitor becomes reasonably wealthy. Still, it does not alter the janitors’ behaviors, nor has it altered your ability to attract janitors. So I think ESOPs should be used very wisely to attract and retain talent.

Ganesh: When you negotiate cash versus ESOP with a new hire, is that something that you actively track to evaluate a candidate’s entrepreneurial energy or commitment to that role? And is it okay if somebody chooses more cash versus equity? Or do you favor somebody who chooses a higher proportion of equity?

Hari: The way a candidate negotiates compensation tells you a lot about them.

If you’re a startup, you’re looking for people willing to take risks and negotiate compensation, but more strategically. If somebody would want to negotiate a cash compensation, it can be challenging. Suppose the employee is making INR 1 crore in a company now, and the employee wants a 15% increase. If the employee is unwilling to come in at INR 85 lakh in exchange for ESOPs, that might not be a good hire. I think the way a person negotiates compensation is one of the most significant indicators of how this person will behave in a team and the company later on.

Ganesh: Are there any specific behaviors that you look for that founders or HR heads can keep in mind when hiring very senior folks?

Hari: A candidate might ask for exceptions. For example, suppose the startup’s policy has only economy class travel, and the candidate is from a big company and is senior enough and is used to business class travel. In that case, he will come and negotiate to ask for that. This is a big red flag. Other red flags are employees who ask for exceptions on leave or other things like a very liberal severance package if they are asked to quit due to non-performance. Another red flag is being inflexible on cash compensation and not seeing the value of stock options.

Ganesh: Are you seeing that many candidates now are taking an interest in and spending time understanding the company’s ESOP policy? Do you see candidates asking about the nuances?

Hari: No, I think that trend hasn’t changed. Even at very senior levels, employees are pretty ignorant of the ESOP policy. They accept and sign on the dotted line for stock option plans without understanding or knowing what it means or even asking intelligent questions. So the ratio would be even less than 1:100 if we count the people who truly understand how stock options operate and have a sense of that.

Ganesh: There was a time when founders accepted term sheets they didn’t understand, right? Now, founders are very savvy about the term sheets. LetsVenture open-sourced all these documents. We are now doing that for ESOP policies, and we hope we can get things to change. Let’s talk about ESOP liquidity. Some companies use their balance sheet and do “ESOP buybacks,” where canceled options are paid out as a bonus. And then, others are allowing third-party investors or existing investors to come and buy out ESOPs. Do you have any view on which of the two is better from a company’s perspective? Does it give more validation for an employee when a third-party buyer pays for it versus the company compensating with its balance sheet?

Hari: Liquidity events of any kind give employees some degree of confidence that they are not holding just a piece of paper. I think it does not matter how that liquidity comes; it could come via a third party at a stage where the startup is raising money, and new investors are coming in and putting in money to buy out some options. Multiple ways of ESOP liquidity are possible. And I don’t think from an employee’s perspective, any of this matters.

From a company’s perspective, some things may matter. For example, when a company buys back stock options, they are depleting their cash, and why would they want to deplete the cash if they could put the cash to other uses.

Ganesh: To understand your perspective, when should a liquidity event be organized for employees? Of course, it may change from different companies in terms of the stage and maturity of the business, right? Maybe a Series B or C founder may think to operate differently from a unicorn, but are there any general principles that you have in mind on when ESOP liquidity should be offered, and whether it should have a regular cadence, or should be based on some milestones of the company.

Hari: That’s a difficult question to answer. I think the only principle behind a decision like this should be fairness, which is that some individuals have taken a risk and joined you, hoping that they will make money in a reasonable time. And sometimes, a good time can keep on getting extended. I think when the reasonable time keeps on getting extended, that’s when founders should ensure some liquidity for early employees. It does not matter if you are at Series A or B; if some liquidity was promised in a four or five-year timeframe, and it has not happened till 6 years, founders should try and create liquidity events.

Ganesh: Are there other trends that you’re seeing or any trend that you wish was happening or reform that you feel we should be working on?

Hari: I want only one reform – change in the taxation of ESOPs. I don’t think stock options should be taxed on exercise; they should only be taxed at the time of sale. Stock options being taxed on exercise goes against the very grain of encouraging startups and encouraging people to work with startups.

ESOP & CAP Table

Management simplified

Get started for free